1622975232000

Electrical Stimulation Treatments: Scientifically Tested for Improvement in Fibromyalgia & Potential Application in Other Functional Somatic Syndrome

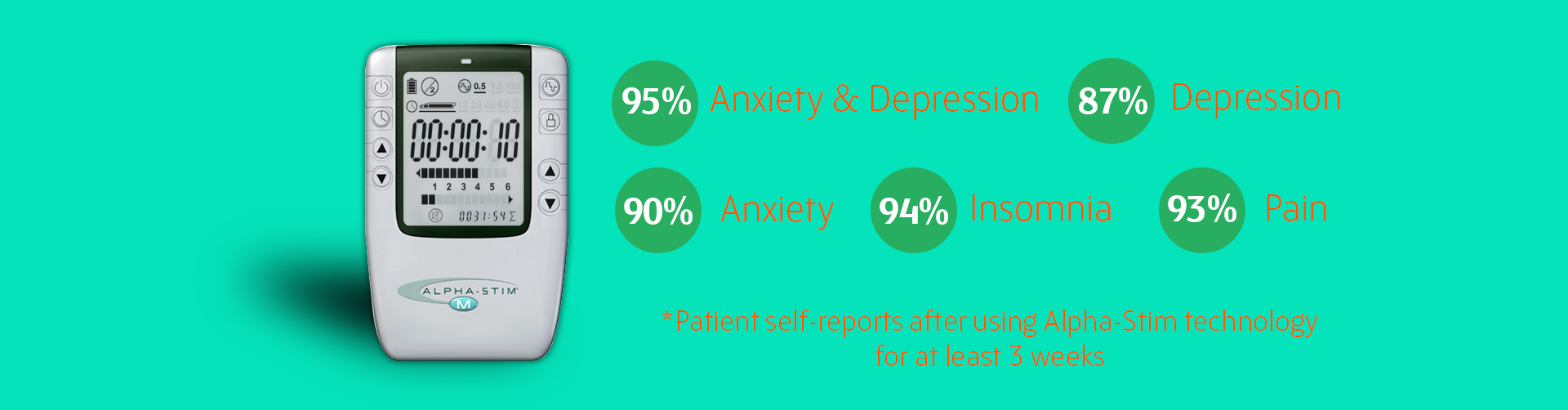

Fibromyalgia has been linked with other conditions referred to as functional somatic syndromes (FSS). FSS are characterized more by symptoms (such as pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbance), suffering, and disability rather than by disease-specific, demonstrable abnormalities of structure or function.1 FSS include irritable bowel syndrome, chronic fatigue syndrome, tension headache, temporomandibular joint dysfunction, and fibromyalgia among others.2 These conditions are also commonly associated with anxiety, depression, and trauma-related disorders.3 There is an ongoing debate as to whether FSS’s should be defined as separate entities or as one syndrome.3 A substantial overlap exists between the individual conditions, patients with one condition frequently meet criteria for another, and patients with FSS’s share non-symptom characteristics (such as sex, emotional disorders, trauma histories, and difficulties in patient-provider relationships).2 Thus, a more dimensional classification of FSS may be more productive than the assessment of individualized conditions which may improve future treatment options. Medical management of FSS’s historically rested on six steps:1. ruling out the presence of diagnosable medical disease2. searching for psychiatric disorders3. building a collaborative alliance between the patient and provider4. making restoration of function the goal of treatment5. providing limited reassurance6. prescribing cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for patients who have not responded to the aforementioned steps.1Furthermore, a comprehensive, bio-psycho-social approach to the management of FSS may include the use of complementary modalities, such as electrical stimulation treatments, to augment conventional treatments.4 Conventional medical therapy is fairly ineffective for these cases, and tend to result in frustrated providers and dissatisfied patients. Providers involved in the treatment of fibromyalgia are always looking to include modalities in their clinic armamentarium that have demonstrated to be effective, safe, and non-invasive.The use of electrical stimulation for the relief of physical and emotional distress is not a new phenomenon. In fact, there are early written accounts of a physician using electric eels to treat the Roman Emperor Claudius’ headache.5 Today, electrical stimulation treatments are relatively safe, easy to use, and the newer technologies, such as micro-current electrical therapy (MET) and cranial electrotherapy stimulation (CES), have research evidence to support their efficacy in the treatment of fibromyalgia.6,7,8 CES has been around for over 60 years, and was originally known as “electro-sleep” in Europe. CES devices deliver modified square-wave biphasic stimulation at 0.5Hz and 100uA through the electrodes placed on the patient’s ear lobes. An average CES session lasts between 20 to 60 minutes. Several rigorous double-blinded clinical trials have been conducted with CES for fibromyalgia. Lichtbroun and colleagues (2001) found that CES yielded about a 28% reduction in tender point scores and 27% reduction in self-reported overall pain level, which is comparable to findings in medication studies.6 Cork and colleagues (2003) found that CES had significant effects on pain intensity and mood, but not on function.7 Taylor and colleagues (2013) found that CES had a greater decrease in average pain and a decrease in activity in the pain processing regions of the brain.8Research has also indicated that the use of MET can complement or improve results of the CES. MET is provided directly to the body of the patient suffering from pain either through hand-held probe electrodes or self-adhesive electrodes. The probes of the MET device are repositioned every 10 seconds following a beep from the device, and are placed through the area of the pain complaint. Kulkarni (2001) investigated the use of CES and MET in combination in treating complaints of pain and found that patients received significant relief between 33-94%.9 Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) devices differ from CES or MET in that it applies electrical currents on the surface of peripheral nerve route sites on the extremities or other non-cranial areas. It is the distinct waveform of the CES and MET that differentiates them from other devices. Through periodic, slow reversal of the polarization of the DC current, the CES and MET waveform is able to inject a spectrum of low frequencies into the neuronal tissue to match frequencies with different receptors, thus activating them in a way similar to medication management.The Alpha-Stim® devices are FDA approved for the treatment of pain (MET) and depression, anxiety, and insomnia (CES). Thus, the FDA requires a prescription by a licensed mental health or health care professional to legally obtain and use these devices in the U.S. Furthermore, there has been some debate about whether use of these devices are within the scope of practice in mental health. Per consultations with U.S. licensing and ethics boards, there is nothing in the law or ethical code at this time about the use of these technologies. More recently, there has been some debate as to why the FDA re-categorized CES devices as Class III, which requires extensive and expensive trials for market approval. These devices continue to be subjected to rigorous study and evaluation by the international medical community. There have been several mechanisms of action of electrical stimulation treatments that have been proposed in the research, including: Deactivating brain regions associated with hyperactivity consistent with various disorders (CES)Increasing alpha-wave activity and decreasing delta and beta-wave activity (CES)Increasing the concentration of neurochemicals (such as beta-endorphin, serotonin, and melatonin) and decreasing cortisol in the brain10 (CES)Increase in ATP which moves more amino acids into the area and increases protein synthesis at the site treated11 (MET).To date, there have not been any significant lasting harmful side effects or worsened pain as a result of treatment reported in the past research literature.12 Side effects (all less than 1%) reported from CES and MET include vertigo, headache, nausea, and skin irritation at the site of the electrodes. Vertigo and headache usually occur when the intensity of current is too high on CES for the individual. These symptoms will resolve when the current is decreased. Alternating sites for placement of electrodes will decrease irritation at the electrode site that may occur when using MET. There is also no evidence to suggest that the CES or MET is habit forming or may lead to addiction. Caution is advised during pregnancy and with patients with older pacemaker models circa 1998. It is also not recommended that patients operate complex machinery and/or automobiles during the treatment. The current review shows that CES and MET can stand together or alone as significant, complementary modalities for the treatment of fibromyalgia and other functional somatic syndromes.BiographyDavid Cosio, PhD, is the psychologist in the Pain Clinic and the CARF-accredited, interdisciplinary pain program at the Jesse Brown VA Medical Center, in Chicago. He received his PhD from Ohio University with a specialization in Health Psychology in 2008. He completed a behavioral medicine internship at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst Mental Health Services and a Primary Care/Specialty Clinic Post-doctoral Fellowship at the Edward Hines Jr. VA Hospital in 2009. Dr. Cosio has done several presentations in health psychology at the regional and national level. He also has published several articles on health psychology, specifically in the area of patient pain education. There is no conflict of interest to report at this time.References1. Barksy, A. & Borus, J. (1999). Functional somatic syndromes. Annals of Internal Medicine, 130, 910-921.2. Wessely, S., Nimnuan, C., & Sharpe, M. (1999). Functional somatic syndromes: One or many? The Lancet, 354, 936-939.3. Afari, N., Ahumada, S., Wright, L., et al. (2014). Psychological trauma and functional somatic syndromes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosomatic Medicine, 76, 2-11.4. US Department of the Army, Office of the Surgeon General. (2010) Pain Management Task Force Final Report. Available at:. Accessed September 28, 2015.5. Edelstein, L. (1967). Ancient Medicine. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins Press.6. Lichtbroun, A., Raicer, M., & Smith, R. (2001). The treatment of fibromyalgia with cranial electrotherapy stimulation. Journal of Clinical Rheumatology, 7, 72-78.7. Cork, R., Wood, P., Ming, N., et al. (2003). The effect of cranial electrotherapy stimulation (CES) on pain associated with fibromyalgia. The Internet Journal of Anesthesiology, 8.8. Taylor, A., Anderson, J, Riedel, S., et al. (2013). A randomized, controlled, double-blind pilot study of the effects of cranial electrical stimulation on activity in brain pain processing regions in individuals with fibromyalgia. Explore, 9, 32-40.9. Kulkarni, A. (2001). The use of microcurrent electrical therapy and cranial electrotherapy stimulation in pain control. Clinical Practice of Alternative Medicine, 2, 99-102.10. Kirsch, D. & Marksberry, J. (2015). The evolution of cranial electrotherapy stimulation for anxiety, insomnia, depression and pain and its potential for other indications. In: Rosch, P. (2015). Bioelectromagnetic and Subtle Energy Medicine (2nd ed). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.11. Mercola, J. & Kirsch, D. (1995). The basis for microcurrent electrical therapy in conventional medicine practice. Journal of Advanced Medicine , 8, 107-120.12. Young, R., Kroening, R., Fulton, W., et al. (1985). Electrical stimulation of the brain in treatment of chronic pain: Experience over 5 years. Journal of Neurosurgery, 62, 389-396.